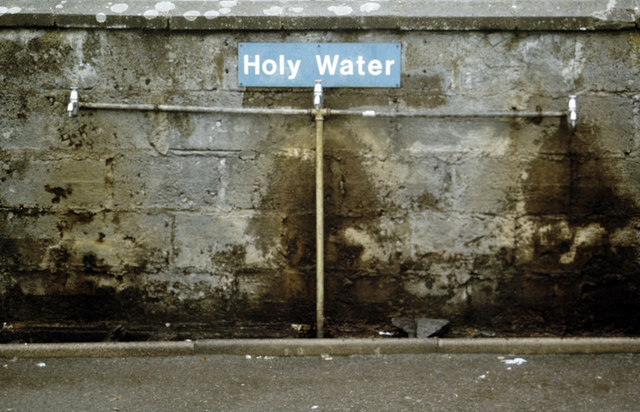

In a church, holy water is primarily stored in a baptismal font where it is used for baptisms. These fonts are typically located near the entrance to the church or in a separate room called the baptistery. Smaller vessels, called stoups, are placed near the doors to the church so that individuals can bless themselves with the sign of the cross as they enter. This is done as a sacramental to recall their baptism. Liturgies may also begin with a Rite of Blessing and Sprinkling Holy Water in which the priest uses an aspergillum to sprinkle the congregation with holy water. This practice is called aspersion, a name which comes from the Latin aspergere meaning “to sprinkle.”

In the Middle Ages, the faithful attributed great power to holy water both in terms of blessing and repelling evil. For this reason, holy water fonts were covered and locked to prevent the water from being stolen and used for magical practices. While this is no longer the case today, holy water is still treated with reverence and in a special manner. It cannot be disposed of via ordinary plumbing but, instead, is poured into a sacrarium, a special sink which drains directly into the ground.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed